City of El Paso voters will decide whether to spend nearly $272.5 million on three bond proposals, the vast majority of which is set aside for streets but would also fund new parks and planning for climate impacts.

About 90% of the 2022 Community Progress Bond — $237 million — is earmarked for Proposition A, which includes repaving and reconstruction projects on El Paso roads and streets and some safety improvements such as lighting.

Another 8% goes to Proposition B, which asks for $20.8 million for parks, including $10 million for an accessible park for children of different abilities, $5 million to install shade structures in parks across the city and $5 million for the continuation of the Neighborhood Improvement Program. That program allows neighborhood associations to directly apply for small-scale projects from the city, such as trash cans or picnic tables at area parks.

Finally, Proposition C asks for $5 million for a “climate action and urban plan and implementation,” which is 2% of the bond.

Each area — streets, parks and climate action — appear separately on the ballot. Voters can approve or reject each item individually. If an item is rejected, a 2015 state law prohibits the City Council from issuing debt to pay for the project for next three years. There is an exception, however, if the projects are required to comply with federal or state law.

Early voting for the Nov. 8 election runs from Oct. 24 to Nov. 4.

Here are answers to some frequently asked questions regarding the proposed bond put together by El Paso Matters.

In Proposition A, what streets and roads are being considered and what is the timeline?

The $237 million would be spent over a period of 10 years.

The city has just over 6,000 streets, the vast majority of which (about 5,000) are classified as residential streets. Since 2013, the city has resurfaced close to 480 streets.

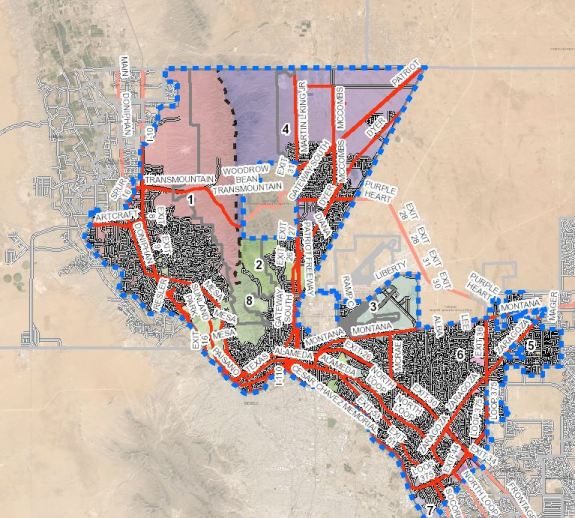

The biggest budget item is $135 million to resurface, and in some cases rebuild, segments of the city’s most-used arterial roads — larger streets frequently traveled to cross the city. The city has completed work on four of the 50 most-used roads, leaving the other 46 to be funded by the bond. A majority of the repavement the city identified is in Central and East El Paso. There are 188 arterial roads in the city.

Another $35 million is earmarked for residential streets, but exactly which streets remains undetermined. If the bond is approved, the City Council every two years would vote on which residential streets to prioritize for repaving.

The criteria, deputy city engineer Yvette Hernandez said, would include the streets’ condition based on the citywide pavement condition index study. The city would also take into consideration if the street is in a neighborhood that requires multiple streets to be repaved at a time, and if the project is selected for utility construction.

“I know a huge frustration when we’ve paved something (is) just six months later, you’re driving over plates,” Hernandez said. “We’re going to make sure to coordinate with utilities so that we know what their plans are for their infrastructure, and we’re aligning it with the streets that we have selected.”

Top priority neighborhoods would have poor roads that are clustered together and would also be in line for utility upgrades.

Another $52 million will go to connectivity, which Hernandez said is extending roads such as Montwood Drive to ease congestion.

The remaining Proposition A funding would go to other improvements like extending sidewalks and installing lighting. Any surplus will go to safety improvements such as restriping lanes or improving intersection visibility.

Why does the city need additional debt to fix roads and how much does the city already spend?

“Streets are historically underfunded,” Hernandez told a crowd at a community meeting at a Northeast Denny’s in late September.

“We need $44 million per year,” Hernandez said. “What we currently have now through our Pay Go fund is $10 million, leaving a $34 million gap.”

Hernandez said bond approval would better close the gap, and would prevent further deterioration on El Paso’s main roads and more expensive fixes in the future.

This year, City Council resumed spending from the Pay Go fund, which uses money generated from franchise fees on residential water bills paid for by water customers, after the funds were redirected during the pandemic. The city will use $7 million from the Pay Go fund and the bond would add another $3.5 million, totaling $10.5 million each year for repaving residential streets.

What roads are excluded?

Many of the 188 arterial roads in El Paso are not city-owned, but are maintained by the Texas Department of Transportation, and cannot be considered under the proposed bond. These include: Mesa Street, Doniphan Drive, Dyer Street, McCombs Street, McRae Boulevard, Montana Avenue, Woodrow Bean Transmountain Drive and Zaragoza Road.

In Proposition B, what is an all-abilities playground?

Ben Fyffe, the city’s managing director of Cultural Affairs and Recreation, described the vision as an accessible “megapark” that creates a space for children with and without disabilities to play together. The base of the park would not be woodchips, but a flat, soft surface to better push wheelchairs or strollers through.

“For anybody with mobility issues or special needs, these playgrounds are designed to be able to accommodate them, as well as people who may not have those needs at the same time,” Fyffe said at a northeast community meeting. “If you’re a family that might have a child with particular needs, and your other children do not, you’re not having to segregate them, you can actually enjoy these all together.”

Park projects would be completed on “a faster timeline” than the 10 years required for road improvements, Hernandez said.

There are three nearly-complete all-accessible playgrounds at Shawver Park in the Lower Valley, Joey Barraza and Vino Memorial Park in the Northeast and in the second phase of the Eastside Sports Complex, Fyffe said.

Parts of the new accessible playground’s $10 million cost may be covered by federal or other grants, Fyffe said.

Where will the accessible playground be located?

City officials said they have not selected a site.

“If this funding is approved, we would then be able to start planning this,” Fyffe said. “Right now, we don’t have a specific location in mind, because we want to actually have more conversations and figure out where this makes the most sense for this park to be accessible from around the city.”

How many new shade structures will be installed?

Of the city’s 177 parks, 77 have canopies that cost roughly $275,000 each. The city is considering another 15 to 18 shades.

“The intention here is to put shade structures within every single one of the districts,” Hernandez said. “And the criteria is really looking at the density population, the permit use, making sure that we’re strategic about putting the shade structures where they’re needed most.”

What does Proposition C entail?

The proposition is split into two parts: a $1 million feasibility study to identify projects to reduce climate impacts and then $4 million to implement some of these proposed projects.

The study will examine flooding, heat mitigation, traffic congestion and mobility around the city, and will offer data to ensure the money is being spent correctly for future projects.

“We know in our hot desert sun, we might have a walkway, but we’re not going to use it if there’s no shade and trees. So also looking at tree canopies, looking at more open space to mitigate that heat island effect,” Hernandez said.

Future projects under consideration are adding bike paths and pedestrian-friendly walkways or compensating homeowners for solar power use and efficiency upgrades.

At an Oct. 3 bond meeting, city Rep. Cassandra Hernandez said the plan makes El Paso a competitor for federal dollars, adding that the city needs to inventory solutions and assign priorities to climate threats such as extreme heat and flooding.

“With any federal grant program, if you don’t use it, you lose it and you lose it to other communities,” Hernandez said. “If you don’t have a plan, if you don’t have the environmental studies, if you don’t have the identified projects, other communities are going to take those dollars.”

She said El Paso is already playing catch-up to the other major Texas cities that have climate plans in place.

How does the new debt impact property taxes?

Yvette Hernandez said the potential impact to property taxes is $5 per month — or $60 per year — starting smaller in early years and gradually increasing, according to city estimates.

“We’re not going to ask for all $272 million at the onset, because we still have design planning. And then we have construction. So we’re making sure that we’re only issuing the debt as we need it,” she said.

What is the status of past bonds?

In 2012, El Pasoans overwhelmingly approved two quality of life bond requests totaling $473 million, as well as a proposition to increase the hotel occupancy tax to help fund the Downtown ballpark. All three proposals received a significant majority of the vote — 75%, 72% and 60%, respectively.

While a majority of park upgrades and El Paso Zoo improvements from the 2012 bond are complete, Hernandez said, three Downtown signature projects remain unfinished.

The most controversial is the $180 million Downtown arena, which has been stalled while millions of dollars in litigation have been spent over its planned location in the Duranguito neighborhood. The city recently hired another firm to conduct an $800,000 re-evaluation of the proposed site, the size and type of venue that should be built and the new cost of the project.

The other two signature projects that are under construction have grown in scope and price since they were first approved by voters.

The original cost of construction for the Mexican American Cultural Center was $5.7 million, but the adjusted budget is nearly three times that at $16.5 million. About $7.3 million of the new total cost comes from investments and savings on other capital projects, city officials have said.

The children’s museum, to be named La Nube: The Shape of Imagination, was estimated to cost $19.2 million, but the project ballooned under a public-private partnership spearheaded by the El Paso Community Foundation. The most recent adjusted budget for the city’s portion of 70,000-square-foot museum is $39.2 million, with a total cost estimated at about $70 million. The museum is expected to open in fall 2023.

In 2019, El Paso voters passed the $413 million public safety bond requesting new funds for police and fire facilities and additional vehicles with nearly 60% of the vote. However, only 31,562 voters cast a ballot in that bond election, meaning the spending was determined by just 6% of the county’s registered voters.

The city broke ground on two projects for that bond this year: The first was in January for a Westside fire station and then in February on a far Eastside police regional command center. The largest project, a new $90 million police headquarters, has been deferred since March 2020, according to the city’s map of capital improvement projects. City spokesperson Laura Cruz-Acosta said the project is over budget and therefore is on hold while alternatives are considered.