In the winter of 1917, fear of a typhus outbreak prompted a quarantine policy along the United States-Mexico border. For over 40 years, this United States border quarantine mandated the forcible bathing of Mexican border-crossers (and their belongings) in harsh and dangerous chemicals including kerosene, Zyklon B, DDT, and sodium cyanide.

Although the 1917 quarantine policy is now a little known piece of border history, there are lessons to be learned and a potent legacy that remains.

“HUNDREDS DIRTY LOUSEY DESTITUTE MEXICANS ARRIVING AT EL PASO DAILY / WILL UNDOUBTEDLY BRING AND SPREAD TYPHUS UNLESS A QUARANTINE IS PLACED AT ONCE,” read a telegram sent by El Paso Mayor Tom Lea Sr. to the U.S. surgeon general on June 17, 1916. Lea’s plea would result in a sweeping quarantine policy that codified racism and classism along the southern border in one of the most dramatic and shameful actions of U.S. history.

A little-known piece of history

Discoveries of the spread of typhus by lice, combined with eugenicist ideology and widespread prejudice about “dirty Mexicans,” prompted the construction of border inspection stations in 1917, where Mexican entrants would be stripped naked, examined by border officials, and drenched in chemicals before being allowed to gain entry to the United States. These practices were disproportionately carried out on low income border-crossers, because officials were allowed to use their discretion with who would be subject to bathing.

Although there was widespread rioting (known as the Bath Riots) when the quarantine was first put into effect, the efforts of the rioters were unsuccessful, and the policy remained in place well into the 1950s. Indeed, there is little information available of when this policy formally ended, with some braceros describing receiving delousing DDT baths in the early 1960s.

Inequity and abuse was rendered invisible in the wake of the 1917 quarantine policy. There has never been a major research study of the health effects caused by widespread chemical baths given to Mexican and Mexican-American border crossers, nor is there information on the collective trauma caused by forcible public bathing of many thousands of border crossers.

In times of widespread fear, dramatic actions are taken that carry vast implications for future generations. The minimization of harm can often fall by the wayside.

Commonalities between 1917 quarantine and today

Although the circumstances of the 1917 typhus outbreak are markedly different from those of today’s COVID-19 pandemic, there are some commonalities worth considering.

Public health crises tend to affect communities disproportionately based on axes of inequality, such as race, socioeconomic status, age, indigeneity, and ability. This tendency is playing out as much today as it did 100 years ago, with the most vulnerable community members being exposed to the most risk and least support, and infection/death rates that reflect this heightened risk.

Furthermore, fear of illness and infection often foments nationalistic and racist ideology, something we’re seeing today with increased abuse and harassment of Asians as they are villified and blamed for coronavirus.

Information is slowly emerging about the ways in which communities of color are disproportionately being exposed to and dying from COVID-19.

In Illinois, 43 percent of those who have died from the disease are African-American, despite only comprising 15 percent of the state’s population. In New York City, Hispanic/Latino people account for 22.8 percent of COVID-19 deaths, and black/African-Americans account for 19.8 percent of deaths. In Mississippi, black Mississippians account for 56 percent of infections and 72 percent of COVID-19 deaths.

Heightened risk of exposure is worsened by socioeconomic factors — having the ability to socially distance often falls along racial lines. Nowhere is this more evident than in the criminal justice system, where one’s race significantly influences the likelihood of arrest and conviction. African-Americans are 5.9 times more likely, and Hispanics/ Latinos are 3.1 times more likely, to be incarcerated than whites.

The infection rate in prison and detention contexts can be especially high, due to the close contact inmates experience. At Rikers Island jail in New York City, doctors warn that a public health disaster is imminent, with an infection rate of 3.91 percent, or 39.1 cases per 1000 people, compared to the infection rate of New York City, at 0.5 percent.

Around the country, migrant detainees and groups advocating on their behalf have been pleading with officials to consider release from ICE custody, as social distancing has been virtually impossible at migrant detention facilities, where sanitation materials are scant and overcrowding is rampant, with sometimes 70 migrants cramped into a single dorm.

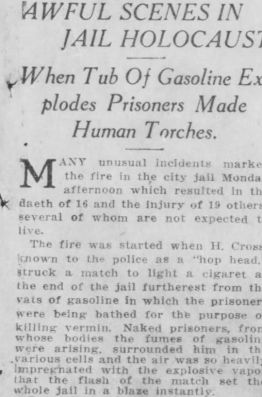

The El Paso ‘jail holocaust’

During the 1917 typhus outbreak, “delousing” chemical baths were first implemented at the jails prior to border-crossings. The forcible bathing of inmates in kerosene at the El Paso jail resulted in a tragedy known as the “jail holocaust,” where at least 25 inmates burned to death.

This event largely inspired the subsequent riots on the bridge, and prompted heightened outrage and fear among border-crossers being subjected to the baths. Then as now, inmates were exposed to heightened risk and minimal protection, serving as a testing ground for public health protocol.

It’s worth noting that much of the American public does not know about events like the 1917 border quarantine policy, the bath riots, or the jail holocaust. These events have been forgotten, or even actively suppressed and removed from history lessons, in part because they are shameful, and tie American history to ideologies and practices that later inspired Nazi Germany. Zyklon B, the same chemical applied to the clothing of border-crossers in El Paso, was used for the mass murder of Jews.

The old adage, ‘Those who do not know history’s mistakes are doomed to repeat them’ is an appropriate warning as the United States collectively navigates another major public health crisis.

Suggested additional reading on this topic:

David Dorado Romo, Ringside Seat to a Revolution: An Underground Cultural History of El Paso and Juarez, 1893-1923 (El Paso: Cinco Puntos Press, 2005).

Alexandra Minna Stern, Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America, 2d. ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015).

Alexandra Minna Stern, “Buildings, Boundaries, and Blood: Medicalization and Nation-Building on the U.S.-Mexico Border, 1910-1930,” The Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 79, No. 1 (Feb., 1999), pp. 41-81; Duke University Press

Cover photo: Contract Mexican laborers being fumigated with DDT in Hidalgo, Texas, in 1956. (Photo courtesy National Museum of American History)